Larry Ryan just wanted to do it right.

His company, Ryan Lawn & Tree, which ranks No. 45 on Lawn & Landscape’s 2020 Top 100 list, started the transition into an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) in 1998. After 20 years of gradually working itself into becoming fully employee owned, Ryan says his company now recruits with an excellent sales pitch: Employees can become fully vested in the company after six years.

“We could’ve done it faster but if we would’ve sold out at a certain price when we were small, the payments were smaller in relationship to the total revenue,” Ryan says. “We could’ve asked for a higher interest rate. We’re just old farmers and making money is not what we’re here for. We get more satisfaction seeing really good people work together rather than getting rich.”

There’s a lot a business needs to do before becoming an ESOP company. From managing the specific costs of making this leap to ensuring your company is even ready, Ryan has a few recommendations for anyone interested in following his lead.

First thing’s first.

Ryan didn’t start the transition into an ESOP until his company had been in business for 11 years. He wanted to make sure his company was both large enough for an ESOP and had been building the right culture to embrace the plan.

“You really have to be a growing company to make it work,” Ryan says. For reference, Ryan says a company would probably need to be around $5 million in annual sales to make this work. He also says employees generally take around three years to fully buy in to a company’s culture, though it only takes one year before an employee becomes eligible to get into an ESOP.

Ryan says that some employees may always be hazy on the details, even years down the road of working for the company, so they might not get involved. But generally, he estimates most of his employees sign up after two years of working for the company.

“Because we’ve integrated everything together and we’re truly committed to our people, even when we were less than 100%, they bought in,” Ryan says. “If you have a bunch of bad people who do not feel good about the company, it is not a good situation. If you do it well, it will certainly pay off.”

Finding the right people.

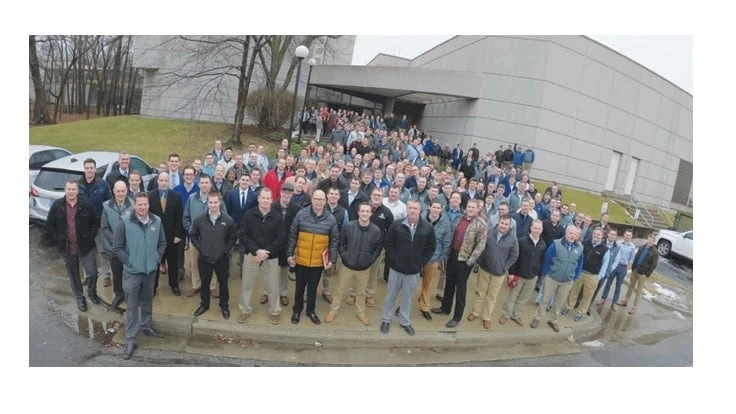

Of course, Ryan says recruiting is a key element to this. He says they have 315 employees from 69 different universities, and not all of them are horticulture grads. Ryan says companies need to figure out how to find employees in places they might not ordinarily recruit. Ryan himself spent time in the restaurant business, for example.

“Early on, we brought in some gifted and very sharp people,” Ryan says. “We almost don’t care about what the degree is in. We care about where their heart is.”

When the company started 33 years ago, Ryan was his one – and only – employee. Two years later, he hired his first full-time worker, who is still with the company all these years later. Ryan says that companies must be willing to show employees that they’re invested in them by offering wages that are higher than most neighboring companies. To do this, Ryan says they charge roughly double per lawn than his largest competitors in the area. Given that 35% of the company’s work is tree care, he also feels that his employees should be fairly compensated for the additional safety precautions they must take.

“You know there are people who won’t pay it,” he says, “But, it hasn’t hurt our growth at all. We need to be charging the value of our product because there’s a lot of risk in what we do.”

Ryan says that recruiting now is easier than before they can talk about the established culture, which for Ryan Lawn & Tree does include a faith-based element. He says this has helped them also recruit high quality people. Plus, he shares that many employees who stick around have well over $100,000 in their ESOP accounts.

“That makes their eyes pop open,” he says.

The next step.

Once a company gets an employee on board, they also need to feel like they’re a part of the decision-making process in order to really buy in.“You get employee buy-in if people truly feel like they’re an owner,” Ryan says. “I own 10 shares of IBM, but the president doesn’t come to me to ask for advice. You try to listen to your employees as much as you can.”

For Ryan, he says that the process should be gradual and deliberate when setting up the ESOP. From 1998 to 2004, they gave 20% of the company to the employees. After that, they sold in two 40% increments over the next several years.

Ryan says they followed the Great Game of Business model, which includes hiring consultants to help set up the ESOP and educate the employees on all the different steps of financial management for the company.

He also readily admits the process isn’t pain-free, and it requires an open mind from the company owner before they launch into an ESOP. They’re expensive and time-consuming to set up, and company leaders need to be ready to do annual payout for people who leave. Ryan says each employee also needs to be looked at as a partner, and if company leadership isn’t willing to do that, things could get ugly.

“(Owners) may not know their place in their own company. You’re going to lose some control,” Ryan says. “If there’s a selfishness in management, they’ll see it. If there’s an arrogance in management, people will see right through it.”

Explore the May 2020 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Lawn & Landscape

- ExperiGreen, Turf Masters Brands merge

- EquipmentShare cuts ribbon on new Maryland branch

- Strathmore acquires Royal Tree Service in Montreal

- In a new direction

- The December issue is now live

- Ignite Attachments debuts 80-inch, severe-duty bucket

- EquipmentShare breaks ground on Roswell branch

- NaturaLawn of America adds Schwartz, Medd to operations team