Nearly everyone in our society values green space. People give a series of predictable responses when asked what makes lawns and gardens important: Landscapes bring beauty into our lives. They provide a connection with nature. They lift the spirit. Some people offer a more utilitarian answer like, “Green spaces provide a place for children to play and families to gather.” And, of course, most people know plants help to cool the immediate area and remove pollutants from the air while releasing oxygen.

Nearly everyone in our society values green space. People give a series of predictable responses when asked what makes lawns and gardens important: Landscapes bring beauty into our lives. They provide a connection with nature. They lift the spirit. Some people offer a more utilitarian answer like, “Green spaces provide a place for children to play and families to gather.” And, of course, most people know plants help to cool the immediate area and remove pollutants from the air while releasing oxygen.

We are now learning there are additional benefits from the managed landscapes that collectively make up green spaces in our cities and towns. These benefits are linked with a move toward sustainability. Economics, depletion of natural resources, environmental pollution and climate change are collectively pushing societies throughout the world to take a holistic view and develop sustainable living systems. Our lawns and landscapes play an important role in the sustainability movement.

Our Carbon Footprint

Global warming is particularly of interest. Most in the scientific community agree that increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations stemming from burning of fossil fuels are driving a “greenhouse effect,” where global temperatures may increase as much as 6 to 7 degrees in the decades ahead, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Temperature changes of this magnitude will adversely impact societies worldwide by causing drastic changes in agriculture, energy use and water supplies – not to mention the inevitable flooding of coastal communities as sea levels rise.

It has become increasingly apparent that the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, our “carbon footprint,” must be reduced. A recent study by U.S. and European scientists predict in The Open Atmospheric Science Journal that stabilizing atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations at the current level of 385 parts per million (ppm) or lower is essential for maintaining the world climate as we know it. This can be done in two ways. The first is to generate less carbon dioxide, e.g., using less energy and driving more fuel-efficient cars. The other is to help offset our carbon release by storing or sequestering carbon in plant systems. This is where green spaces become important. The plants in lawns and landscapes can store large quantities of carbon.

Trees + Turf = Carbon Storage

Plants grow by removing carbon dioxide from the air during photosynthesis and incorporating the carbon into above and below ground tissues. In the eastern and northwestern regions of the U.S., trees often are a major component of the urban landscape and the most obvious potential reservoirs for carbon storage. It has been estimated by the journal Oecologia that healthy trees store about 3,200 pounds of carbon per acre annually, or about 7.4 pounds per 100 square feet of space.

It has just recently been recognized that turfgrasses also play an important role in carbon sequestration. In many urban settings, turfgrasses are the major part of the landscape, particularly when recreation areas are considered. It is estimated that turfgrasses occupy about 165,000 square kilometers in the continental U.S, according to the Agronomy Journal and Environmental Management. Healthy turfgrass can store almost 800 pounds of carbon per acre below ground in soil each year, the Agronomy Journal also reports, which equates to almost 1.85 pounds per 100 square feet of lawn or about one-quarter the rate for trees.

Keeping plants in a healthy state is essential for carbon storage to occur, though. Photosynthesis and growth are the carbon generators. To operate at high efficiencies, they require plants to have minimal problems with diseases and have adequate fertility. With turfgrass, for example, maximal productivity has been linked with regular mowing and leaving clippings in place, reports J. Environ Quality. At the same time, it’s important to manage fungal diseases and insect pests because they can negatively impact the potential of turfgrass to sequester carbon. While less is currently known about the ability of horticultural landscape plants to store carbon, one can safely assume they too will contribute to the carbon storage pool but must be kept in a healthy condition.

Homeowner Help

Healthy, growing landscape plants can offset some of the carbon being generated by individual homeowners. Here is a hypothetical example: A typical gas-powered automobile driven 12,500 miles annually might be expected to release about 2,500 pounds of carbon a year, according to Environmental Protection Agency Emission Facts. A half-acre residence with roughly 50 percent covered in trees could store about 800 pounds of carbon a year. If the remainder of the landscape were turfgrass, it would store another 200 pounds. So, this hypothetical homeowner could offset 1,000 pounds of carbon – 40 percent of their automobile footprint – just by maintaining a healthy landscape.

A common question being posed about green spaces is whether the release of carbon dioxide during maintenance will negate the carbon storage advantages gained with landscapes. With turfgrasses, for example, would gas-powered mowers generate substantial amounts of carbon dioxide and compromise below ground carbon storage? Estimates of carbon use by the Outdoor Power Equipment Institute indicate about 50 pounds of carbon dioxide would be released with frequent mowing over the span of a year. That is a quarter of the carbon being stored in the turfgrass, and a fifth of the total 1,000 pounds of carbon sequestered in the hypothetical lawn cited previously. Bottom line, the system stays positive on balance.

Green $paces

Green space actually may have a monetary value in the future. Recently, the Obama administration announced it would be pursuing regulations that cap the amount of carbon dioxide released in the U.S. If a carbon dioxide cap were put into place, it would be accompanied by a national trading system that would buy and sell carbon credits.

The U.S. system could resemble the one in the European Union. Mandated by the European Parliament and facilitated through private market platforms, such as the European Climate Exchange (ECX), a cap and trade system has evolved. The EU has placed caps on carbon dioxide emissions by energy-intensive industries. If companies exceed caps, stiff penalties can be avoided only if they purchase “allowances” or “credits” in the market. A similar voluntary system already is in place in the U.S. – the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX). Importantly, the CCX includes a carbon offset program, where carbon sequestration contracts are bought and sold. If caps on carbon dioxide emissions are put into place by federal legislation, as expected, carbon sequestered in landscapes may well qualify as a credit activity and have a market value that could be traded.

A Collective Effort

But it will take active participation from all fronts of the green industry to make a positive impact.

Tackling large-scale issues like atmospheric carbon dioxide requires new collaborations between the private sector and public institutions. Recently, Bayer Environmental Science formalized a relationship with North Carolina State University to examine the carbon sequestration potential of well-maintained turfgrass systems in the southeast. Lawn care professionals will play a crucial role as ambassadors to homeowners and local officials. Organizations like PLANET and Project Evergreen will continue to inform and advocate to audiences.

To change public perception of lawns and landscapes as purely aesthetic and utilitarian will require a collective effort. Studying green spaces and carbon sequestration is one step toward sustainability.

Explore the October 2009 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Lawn & Landscape

- LawnPro Partners acquires Ohio's Meehan’s Lawn Service

- Landscape Workshop acquires 2 companies in Florida

- How to use ChatGPT to enhance daily operations

- NCNLA names Oskey as executive vice president

- Wise and willing

- Case provides Metallica's James Hetfield his specially designed CTL

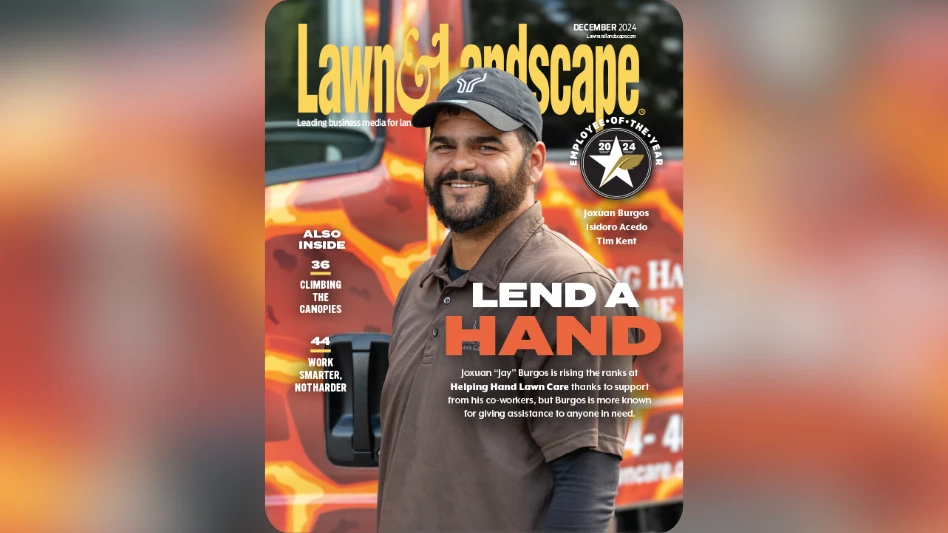

- Lend a hand

- What you missed this week